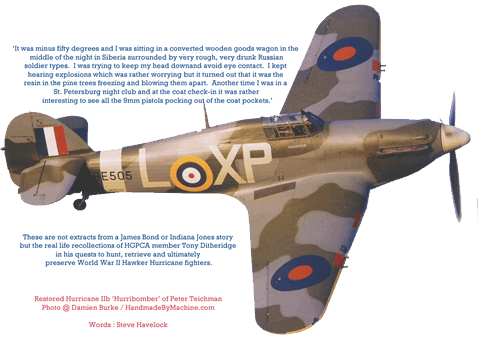

Restored Hurricane IIB 'Hurribomber' of Peter Teichman

Photo : Damien Burke / HandmadeByMachine.com

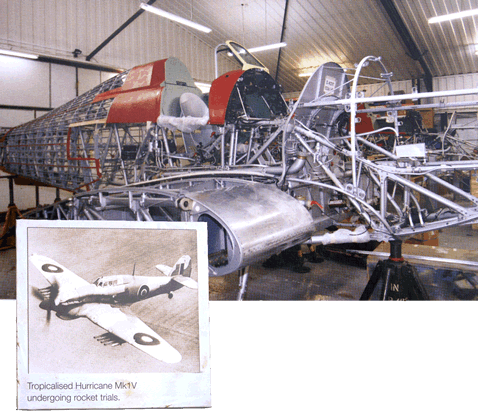

Of the 14,500-ish Hurricanes built between 1937 and 1944 just eleven are flying today, seven of which were meticulously rebuilt by Tony’s company, Hawker Restorations who are currently restoring two more. Sitting behind his red leather topped desk in his photograph and reference book laden office at a secluded private airstrip near Cambridge. Tony told me ‘There are still plenty of Hurricanes left but they are often in desolate inaccessible places. About 3,000 were sent to Russian during the War and most are still there. There are huge lakes in Siberia which froze in the winter. Pilots in difficulty would land on them but in the Spring when the lakes thawed, the aeroplanes sank. The freezing cold fresh water and sit has preserved them very well. We pulled out a Messerschmitt ME110 and it was still covered with paint, the guns were armed, the air bottles were still full and the undercarriage still worked. Getting them out of these places is fraught with problems and then when you do, the cost of re-building them is enormous. Come, I’ll show you what I mean.’ With that, we strutted off to a large grey hangar, inside of which were the skeletal airframes of two Hurricanes and alongside, ready to be installed, a pair of enormous Rolls Royce engines.

My jaw dropped. I had always been under the impression that the Hurricane, with its doped linen covering, bolted together tubular steel frame and plywood cockpit, was a fairly simple and basic aircraft having been more of an evolution of WWI bi-plane technology than anything new, radical and exciting like the Spitfire, with it sexy, slinky looks and all metal monocoque construction. How wrong can you be ? What lay before me was an engineering marvel made up of thousands of perfectly machined components, bolted, riveted and glued together with incredible accuracy.

Tony explained that the Hurricane was designed to be assembled fairly quickly by relatively low skilled people but the manufacture of the parts was very time consuming. The components for the spitfire were easier to make but it was a far more difficult aircraft to assemble. The Hurricane was also far more tolerant to damage than the Spitfire because enemy fire would often pass straight through the fabric and tubes without exploding and any such damage could be more easily repaired in the field.

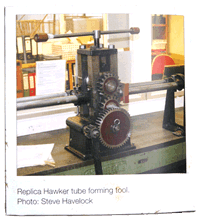

By now, curiosity led me to ask Tony how he became a ‘Hurricane chaser and restorer’ as it certainly wasn’t listed in my school careers booklet. ‘By circumstance and by accident. The story of my life really.’ And what a fascinating life it has been. He was born near Cambridge in 1947 and was quite poorly as a child so missed a lot of early schooling and then left at fifteen to join the Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company as an apprentice instrument maker. They were developing a scanning electron microscope which involved considerable amount of electronics, in with Tony took an interest. Soon he had acquired both mechanical and electronic qualifications which made him an ideal candidate when his company needed someone to go and install their first one in Russia. He recalls ‘it took ten times longer than anticipated but when I got home there was a pile of orders for new microscopes all around the world. I became their export sales and service engineer for Russia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Africa, India, Latin America and Spain. I spent six to eight months of the year away but it was a wonderful experience. Then at 29 I formed my own company, selling and servicing these types of microscopes and also nuclear detections. I bought the property where I am now and turned the outbuilding into laboratories and it was all going rather well. Meanwhile, I had always been into fast cars. I had a supercharged MGTC when I was 17, I built a replica Jaguar D Type, I had a Jaguar XK and all sorts but then decided I wanted to fly and I bought a Tiger Moth over the phone. It arrived disassemble in a container on a snowy Christmas Eve and with the help of some pilot friends we put it together and took it up on Boxing Day. I was then taught to fly I properly but a chap who had 4,500 hours teaching people to fly in the War.’ Tony kept that Tiger Moth for many years but having taken up aerobatics, complemented it with a number of other aeroplanes including Stampes, Pitts, Chipmunks, Zins, Sukhois and Stearmans. Rather unexpectedly, the company who was supplying him with the microscopes threw a spanner in the works so Tony decided to call it a day and restore aeroplanes instead. He recalls ‘ I knew two very talented men who were working for British Caledonian restoring a Sopwith Pup and a Sopwith Camel for Tommy Sopwith’s 100th Birthday (in ’98). It was costing the company a fortune and they wanted out, so these two people jointed me and we continued with the project. Out went the microscopes and in came the planes. We were then approached to build a replica WWI Bristol bi-plane for the Chilean Government and to fly it at one of their air shows, which we did. They were very pleased and we left with an order to build an Avro 504K, an SE5A and a Bleriot. That was really the birth of the aircraft business and those two chaps are still with me.’ Having gained a strong reputation for WW1 aircraft, Tony was appointed to build an SE5 by a serious aircraft collector who also had a passion for WWII fighters. Being pleased with the outcome he asked Tony if he would be interested in looking at some Hurricane wrecks that he had retrieved from Russia. He wanted to restore one of them to keep his Spitfire and Mustang company. Coincidentally, Tony had already acquired a couple of Hurricane wrecks from Russian but when he analysed exactly what was involved in tooling up and how much it would cost, he realised it was too big an undertaking for him. He advised his client that it would make economic sense to build three rather than just one and much to his surprise, he reached for his cheque book and agreed to fund the set up costs for the project. Hence, in 1993, Hawker Restorations was founded. Tony told me ‘Moving from WWI aircraft to the Hurricane was a kind of natural progression for us, just as it would have been historically. We set about restoring one of his planes which he kept and the two that I had found in Russian, which we then sold. Those early days were exceedingly difficult and consumed a huge amount of money. We didn’t have all the original drawings and had to draw many of them ourselves. There are thousands of them and it took years to amass them all.’ Then there were the special tools needed like the hand cranked contraption to turn round tubing into square at all of the bolted connection points. Tony has an exact copy of one of the factory originals. Looking back, he reflects ‘The most difficult and daunting aspect was the manufacture of the centre section and tail-plane spars with the metallurgy and heat treatment involved. The original material is now obsolete and it had some rather unusual properties. You can’t just substitute something else that you think will work. It all has to be stress analysed, tested and approved.’ The rebuilding of these aircraft falls under the watchful eye of the Civil Aviation Authority even though military aircraft were never designed or built to comply with their standards or regulations. Everything has to be meticulously documented. The CAA inspectors can literally point to a screw and demand to know where it came from, what it’s made from, what heat treatment it’s had and who fitted it and if the answers aren’t forthcoming or to their approval, they can shut down the project. Furthermore, they are under no legal obligation to issue a permit to fly and could make life very difficult if they chose to. Tony told me it takes approximately 20,000 man hours to assemble them. In other words, two and a half years for a team of seven. ‘But the first ones took a lot longer than that.’ he adds. ‘We make all the components in batches of at least three and at any one time we always have enough parts in stock to build another complete aircraft.’ When the Hurricanes are finished, before they go off to their new homes, they are wheeled outside, tethered down to a huge concrete block set in the ground, and the rebuilt Merlin engines run un for several hours at different throttle settings, with a final session at full throttle ‘which makes the exhausts run white hot’ says Tony. Now that would be a sight worth seeing. ‘The market for these planes is not as large as you would imagine’ he told me. ‘You need a special class of licence to fly them and have very deep pockets. They cost about £50,000 a year to insure and approximately £2,500 an hour in running costs. And you have to use and maintain them regularly or they will cost you even more.’

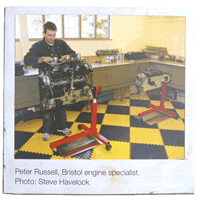

When Tony hit the half century, spurred on by his motor racing friend, John Harper, he decided to try his hand at Historic Formula For in a Lola T200. ‘That was absolutely mad.’ he recalls. He also bought a Cooper Monaco and competed in the BRDC Sportscar series, which he says was ‘good racing, good fun and wall to wall parties.’ He then added a ’58 Cooper T45 and jointed the HGPCA. ‘That didn’t get off to a good start. In my first race at Silverstone I spun on oil and hit the wall, pushing my tibia through my kneecap. But after that, thankfully it went smoother. I really enjoy racing with the HGPCA and I’ve raced at some great circuits like Brno, Most, Imola, Spa and Mogaro but my favourite is Dijon, which really suits the Cooper. It’s challenging and rewarding when you get it right.’ Another turn of events presented yet another opportunity. An ERA was very badly damaged in an accident at Imola and required some expert engineering to sort it out. The local owner knew the quality of work that Tony and his crew turned out and entrusted the rebuild to them. He subsequently asked Tony if he would look after his other racing cars. That got Tony thinking. Along with preparation and maintenance of his own cars, why not start a race shop ? He told me ‘I knew a very competent young engine man and engineer called Peter Russell who wanted to work more with historic racing cars. He agreed to come on board and we formed Hawker Racing at the end of last year. We already had lots of woodworking, metalworking and engineering expertise on site and we had the room, so it made perfect sense. We want to keep it small and friendly with a few good clients and will specialise in Bristol engine cars.’ Tony certainly lives a full and active life but ‘Is there still a Holy Grail ?’ I asked. ‘Oh yes. I want to build a Mosquito. There are none flying and I really think that there should be one flying in the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight alongside the Lancaster, the Spitfire and the Hurricane. Technically they were unique, they were faster than a Spitfire, carried a huge amount of ordinance and they were iconic in their design. There are plenty about bit it all comes down to money. I reckon it would cost £3.5 to £4 million to build one.’ Finally, I asked him what a Hurricane is like to fly. To my astonishment he replied ‘I’ve never flown one. I have had the opportunity but being really honest, although I have flown about fifty different types of light aircraft including many aerobatic aircraft, I wouldn’t trust my experience to fly a Hurricane, And now, at my age, I don’t really want to because I think it would put me under huge pressure. These days, I get more fun out of racing my Cooper than I do flying !’